Why urban greening isn’t a panacea for extreme weather under climate change

Urban greening is often touted as a way to tackle both heatwaves and floods in cities. This includes through green roofs, living walls, vegetated urban spaces, private and community gardens, habitat corridors, bushland and parks.

But our latest research shows that, for most cities worldwide, urban greening can either subdue floods or mitigate heat. It generally cannot do both in one city.

As the climate changes, cities around the world are enduring both heatwaves and floods more frequently. Perth, for example, sweltered through a record-breaking heatwave last month, with six days in a row over 40℃. A few months earlier, Perth recorded its wettest July in decades, with 18 straight days of rain.

Our findings ensure we can plan urban greening projects more effectively to suit cities. So let’s take a closer look at these findings, and the benefits Australia can derive from urban greening.

What we found

Temperatures in cities are often several degrees higher than rural areas, due to the “urban heat island” effect, where the predominance of concrete and steel absorb and retain heat, and there is a lack of cooling by water evaporating from plants.

These same heat-intensifying features are also often responsible for flash flooding in cities, as sealed surfaces can’t act like a sponge to soak up and store rain, unlike the soil they’ve replaced.

To find out whether the benefits of urban greening on cooling and flood prevention hold true, we analysed global climate models and weather information from 175 cities around the world spanning 15 years of daily observations, from 2000 to 2015.

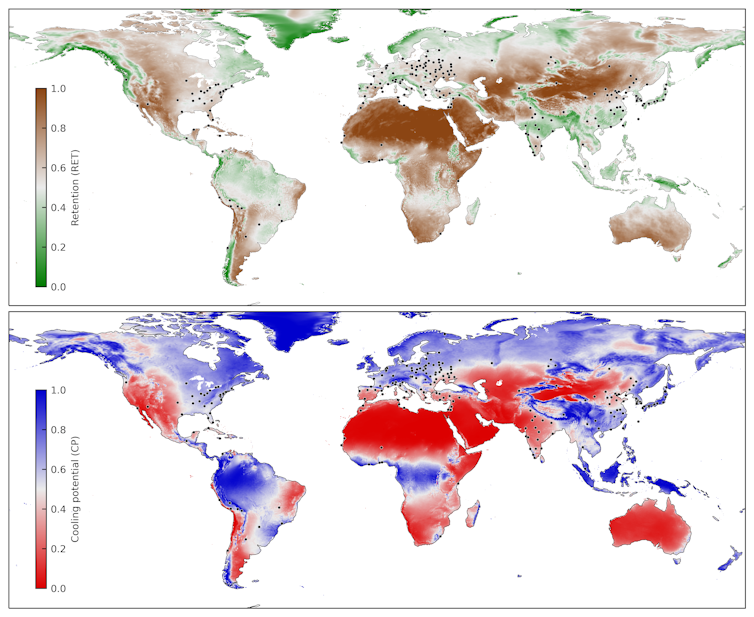

Our results, published in the journal Nature Communications, show the greatest cooling potential occurs where abundant rainwater is available for plants to transpire (release water vapour during photosynthesis). This is common for cities around the Equator and in much of northern Europe.

The cooling potential of urban greening varies with the seasons – it’s more effective if periods of higher rainfall coincide with summer.

Authors. See more detail here, Author provided

In contrast, the greatest potential for water retention by soils, which is crucial for flood prevention, occurs in drier areas where there’s plenty of energy from sunshine, but rainfall is more limited. These areas are common in North Africa, Australia and the Middle East.

Such areas have higher average water retention in the long term, and its potential varies less from season to season. This is because large rainfall events that exceed the storage capacity of the soils and result in water runoff are less common.

What do the findings mean for Australia?

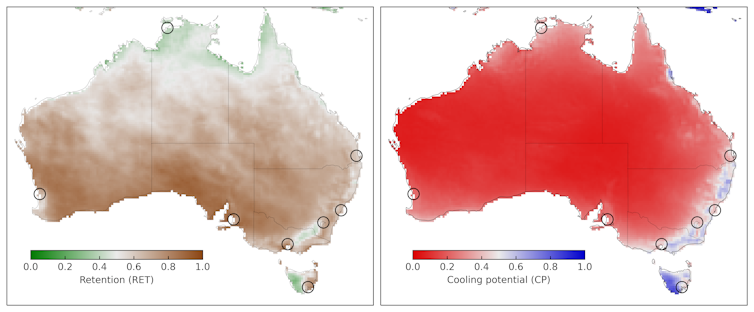

While our findings suggest urban greening can’t reduce both flooding and heat in many, if not most, of the world’s cities, parts of southeast Australia are among the rare exceptions. This includes parts of Melbourne and Hobart.

Melbourne, for example, can endure urban heat island-induced temperature increases of 3℃. City greening initiatives are an important way to mitigate this heat.

On the other hand, Canberra, Adelaide, Perth and Brisbane are “water-limited”, which means urban greening is ineffective at reducing the urban heat island effect. However, because much of Australia has a relatively dry climate which is good for water retention, large-scale urban greening initiatives can help reduce flash flooding in these cities.

For example, Brisbane has lots of sunshine in summer, providing ample energy for evaporation, which often exceeds the amount of available summer rains.

Darwin is Australia’s only state capital that, according to our modelling, would not derive strong stormwater or cooling benefits from urban greening.

This is because Darwin is in an area that transitions between the arid Australian interior and the more humid tropical climates to the north. It doesn’t benefit from the high cooling or water retention performance that comes with either extreme.

Where to from here?

While it seems we can’t assume urban greening can mitigate cooling and flooding at the same time, it’s still an excellent strategy to address either in many places.

Urban greening also has other positive benefits – it provides habitat, filters air and has demonstrable effects on people’s well-being.

However, there are important cost-benefits of these kinds of schemes to consider, both environmentally and economically.

Urban spaces are expensive, and many greening strategies require more complex engineering than traditional buildings. Also, the cooling benefits can only be significant in some areas if irrigation is used, and this is impossible to do sustainably in many parts of the world.

Policymakers worldwide can use our results as a first-pass guide for more local feasibility studies on urban greening. While it’s a crucial planning and climate change adaptation tool, urban greening has to be understood within specific local conditions – one size does not fit all.

Councils, governments, planners and developers need to be fully aware of the benefits and pitfalls before embarking on urban greening projects.![]()

Mark O. Cuthbert, Principal Research Fellow & Reader, Cardiff University; Denis O’Carroll, Professor & Managing Director, UNSW Water Research Laboratory, UNSW Sydney, and Gabriel C Rau, Assistant Professor, Institute of Applied Geosciences, Karlsruhe Institute of Technology

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Main photo by michal dziekonski on Unsplash